Obstructive HCM: Progressive and Often Overlooked1,2

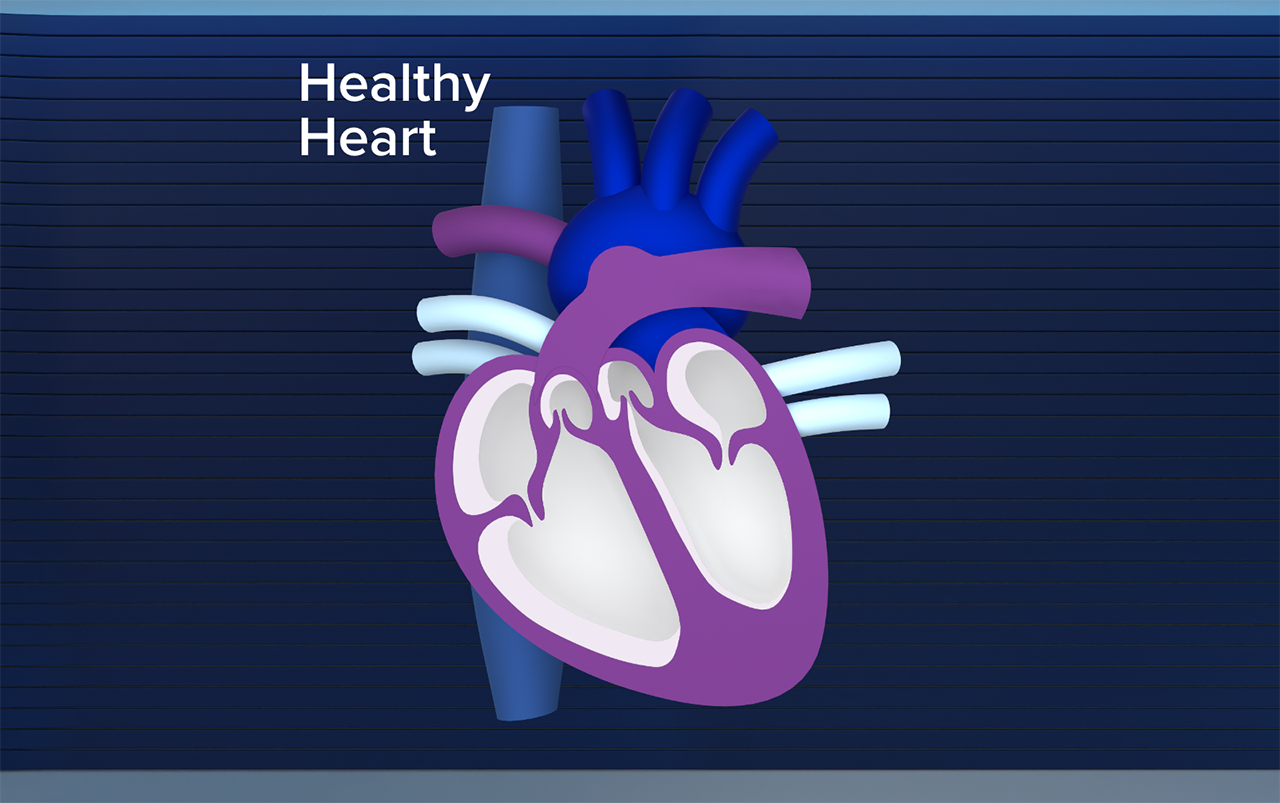

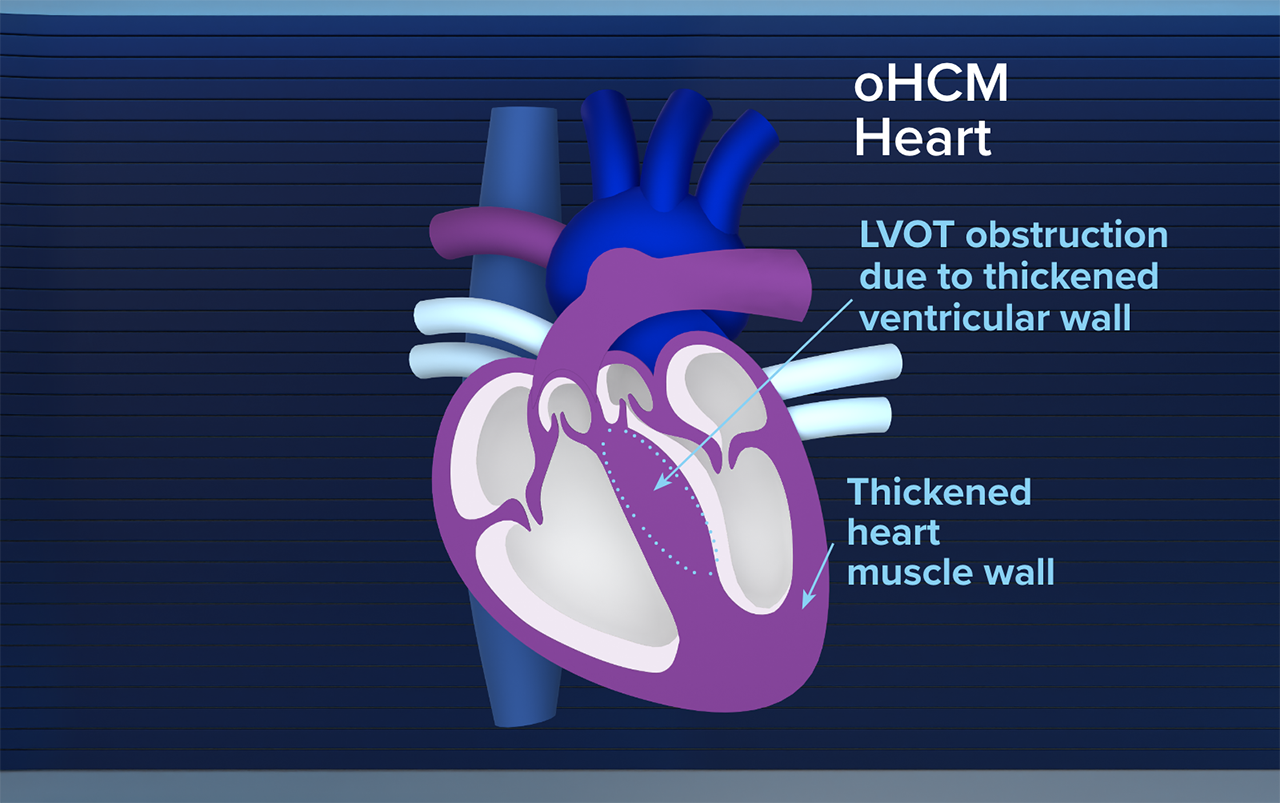

Obstructive HCM causes structural changes in the heart over time3

Changes to cardiac structure–including LVOT obstruction—can lead to symptoms that can significantly impact quality of life1-3

Chest pain

Fatigue

Exertional dyspnea

Palpitations

Dizziness

Syncope

Until recently, treatments have mostly been evaluated in nonrandomized trials1

Prior to cardiac myosin inhibitors, standard-of-care treatments included:

- Primarily symptom management with BBs, CCBs, or disopyramide1,4

- Invasive SRT, recommended to be performed in highly qualified* treatment centers1

| * | Primary or comprehensive HCM treatment centers.1 |

BB=beta blocker; CCB=calcium channel blocker; HCM=hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; LVOT=left ventricular outflow tract; SRT=septal reduction therapy.

The consequences of cardiac structural changes in obstructive HCM are not just symptomatic1

Over time, structural changes can occur, and progressive disease may lead to5,6:

Atrial fibrillation

19%–20%†

of patients5,6

NYHA Class III/IV

heart failure

43%†

of patients5

Stroke or other systemic

thromboembolism

6%‡

of patients6

Mortality

(sudden cardiac death)

<1%†

of patients/year7

| † | Based on a retrospective analysis from the SHaRe registry (N=4591) and a prospective, single-center US observational study from 2003–2013 (N=1000).5,6 |

| ‡ | Based on a four-center observational study in the US and Italy (N=900).7 |

The 2024 AHA/ACC/MS Guideline recommends establishing the presence of obstructive HCM through imaging1

- ≥15 mm wall thickening in the left ventricle (in the absence of another cause of hypertrophy) is required for a clinical diagnosis

- 13–14 mm is required in conjunction with a family history of HCM or a positive genetic test

Per the guideline, obstruction is defined as LVOT peak gradient ≥30 mmHg with or without provocation1

- Assessment of LVOT gradients can help differentiate between HCM subtypes (ie, obstructive vs nonobstructive)

- Genetic testing is beneficial to facilitate the identification of family members at risk for developing HCM

ACC=American College of Cardiology; AHA=American Heart Association; MS=multisociety; NYHA=New York Heart Association; SHaRe registry=Sarcomeric Human Cardiomyopathy Registry.

Current treatments for symptomatic obstructive HCM

Conventional1

The role of treatment options recommended in the AHA/ACC/MS Guideline is that of symptom management. Due to limited evidence from randomized controlled trials, management is often based on nonrandomized or limited data.

CAMZYOS1,8,9

Uniquely targets the source of obstructive HCM.§ The first and only FDA-approved cardiac myosin inhibitor to have a Class 1 recommendation when symptoms persist on 1L therapy.¶ Studied with and without background therapy in 2 phase 3 trials and their ongoing long-term extensions.

Invasive1

Guideline-recommended septal reduction therapy for patients whose symptoms are not relieved by 1L pharmacological therapy.¶

| § | CAMZYOS is an allosteric and reversible inhibitor selective for cardiac myosin that helps to modulate the number of myosin heads in the off state. This reduces the number of myosin-actin cross-bridges that form.8 |

| ¶ | Symptoms include effort-related dyspnea or chest pain and occasionally other exertional symptoms (eg, syncope, near syncope) that are attributed to LVOTO and interfere with everyday activity or quality of life despite beta blocker or nondihydropyridine calcium channel blocker.1 |

1L=first-line; FDA=US Food and Drug Administration; LVOTO=left ventricular outflow tract obstruction.

Consider the next step—complement conventional therapy with CAMZYOS8

References:

- 2024 AHA/ACC/AMSSM/HRS/PACES/SCMR Guideline for the Management of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: A Report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2024;150(8):e198. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000001277

- Naidu SS, Sutton MB, Gao W, et al. Frequency and clinicoeconomic impact of delays to definitive diagnosis of obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in the United States. J Med Econ. 2023;26(1):682-690. doi:10.1080/13696998.2023.2208966

- Stanford Health Care. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Accessed August 12, 2025. https://stanfordhealthcare.org/medical-conditions/blood-heart-circulation/hypertrophic-cardiomyopathy.html

- Olivotto I, Oręziak A, Barriales-Villa R, et al; EXPLORER-HCM study investigators. Mavacamten for treatment of symptomatic obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (EXPLORER-HCM): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2020;396(10253):759-769. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31792-X

- Rowin EJ, Maron MS, Chan RH, et al. Interaction of adverse disease related pathways in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2017;120(12):2256-2264. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2017.08.048

- Ho CY, Day SM, Ashley EA, et al; SHaRe Investigators. Genotype and lifetime burden of disease in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: insights from the Sarcomeric Human Cardiomyopathy Registry (SHaRe). Circulation. 2018;138(14):1387-1398. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.033200

- Maron BJ, Olivotto I, Bellone P, et al. Clinical profile of stroke in 900 patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39(2):301-307. doi:10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01727-2

- CAMZYOS [package insert]. Princeton, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; 2025.

- Garcia-Pavia P, Oręziak A, Masri A, et al. Long-term effect of mavacamten in obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J. 2024;45(47):5071-5083. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehae579

3500-US-2500554 09/25